Behind the Story: The Grand Assault and 19th Century Fencing in New York City

From “The Grand Assault” - An advertisement

displayed at the Fencing Club.

A

Grand Assault at the Park Theater

Mr.

Armstrong of the Knickerbocker Fencing Club will fight a match with the latest

in steam mechanicks for the art of fencing, the Schermitore a vapore, or the

steam fencer. This man sized automaton was developed by the acclaimed Italian

inventor Doctor Cosimo Cervello, who is the creator of the Cervello Steam Boat

that was used effectively in the naval bombardment of Algiers. Dr. Cervello

claims that the steam fencer, a machine of speed and precision, can defeat any

opponent. It has been educated in the use of arms by Count Enrico Strattofenza,

the undefeated Champion of the Italian Kingdom of Naples, who will accompany

the schermitore a vapore as its manager and trainer.

They

will be using the latest technology in the art of fencing, the Fioretto di

pressione, or the Pressure Foil, also created by the eminent Dr. Cervello, who

will attend the match on behalf of his new allegiance to the United States.

|

| From the Century Illustrated Magazine January 1887 |

Fencing was popular among the fashionable

society of New York City. An 1897 Article titled “Fencing Now Society’s Fad” in

the New York Times tells us “Never has fencing been as popular as it is today.

It is the fad of the hour among fashionable folk.” It continues “The list of

fashionable young men who fence is practically endless. Every young man who has

any claim to social distinction has taken a course of lessons from a maître

d’armes.”

And not just among men. Fencing flourished with

society women. Many magazine and newspaper articles of the late nineties

covered the fad of fencing among ladies.

|

| From the New York Times May 2, 1897 |

|

| From Munsey's Magazine 1887 |

The Grand Assault and the

Golden Age of Fencing

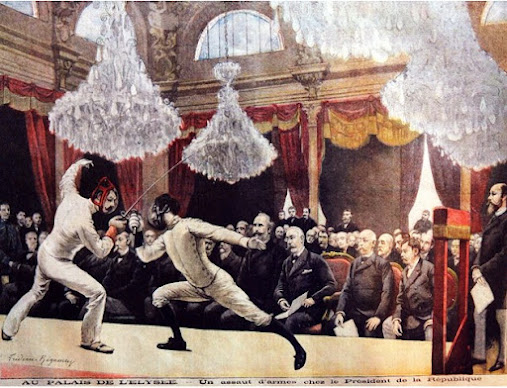

This

was the Golden Age of Fencing, and the paramount event was the Grand Assault. A

Grand Assault was a form of public entertainment that ranged from extensive

exhibitions involving mounted combat and diverse weapons to public challenges

between two well-known fencers. They could draw crowds of thousands of

spectators and many celebrities. Mark Twain was at Gala d’escrime held at the

Fencers Club in New York City, hosting visiting Italian Masters Eugenio Pini,

Agesilao Greco, and Carlo Pessina.

|

| From Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly 1893 |

The English

Military Tournament of 1893

The Grand Assault

could be a complex show, such as the English Military Tournament held at Madison

Square Garden in 1893. This was a traveling spectacle of British soldiers,

putting on a two-week affair with performances daily. Some of the unusual

exhibitions included wrestling on horseback, tent pegging with the lance,

demonstration of transporting heavy gun carriages at high speed, and closing

with a recreation of an attack on a fortified position. One of the main features

was the Balaklava Melee, “in which a dozen of her Majesty’s soldiers show their

skill with singlesticks, causes much merriment in the audience daily, and not a

little howling from the combatants.”

“The Italian play, which has

retained many more of the characteristics of the old rapier-fence, shows much

less difference between the methods used on the pedalina, or fencing-floor,

and those which can be advocated on the “field of honour.”

A French journalist wrote the following in the daily morning newspaper

Le Figaro; “Above all, the purpose of fencing to Italian fencers is combat;

their aim is to hit and not be hit. We, instead, admire, above all, aesthetic

bouts.”

|

| A cartoon of Italian fencing from Frank Leslie's Magazine 1893 |

|

| Professor Agiselao Greco |

Example of such contests was the noted Fencing Master and champion from Italy, Professor Agiselao Greco, who arrived to America to challenge all comers. A New York Times article of November 28, 1893 had a list of challenges that included:

- An advance of 30 points on 100 by sword and saber

- $10,000 dollars for anyone who could touch him on the chest with a dueling sword while he uses an academic sword (foil) for five minutes.

And

in what might have been a rebuke of the courteous French style of fencing, he

offers this challenge:

“I

also accept the challenge of any person who, in ignoring the true art of

fencing, would venture to fight me with boldness and courage, dealing haphazard

strokes, and this for fifteen minutes.”

Greco

might well have been able to withstand haphazard strokes, he was as much a

master of exercise as fencing.

|

| Professor Agiselao Greco |

Regis Senac

arrived to New York City from France. His was the classical French method,

learning his trade as an instructor of fencing in the French army. He came to

the United States in 1872 and opened his fencing school in New York City in 1874.

Senac was noted for fighting three successful duels while in France, and he

continued his contentious ways in New York City. The fencing master sent or

accepted challenges to several of the other masters such as Nicolas, Tronchet

and Jacobi. One of the most celebrated contests of the period was between

himself and the brash Colonel Monstery.

Colonel Thomas Hoyer Monstery was another

fencing master that planted his foil in New York City for a short time after touring

through Mexico and Cuba challenging local fencing masters. Of Danish descent, he

had travelled the world as a fencing master, soldier and duelist. He continued his

challenges in New York, setting up various contests and Grand Assaults and

writing articles on self-defense, boxing and singlestick. Among his notable

students was the swordswoman Ella Hattan, known as the Jaguarina, who fought

matches against men on horseback and with broadsword.

|

| Illustrated Sporting News 1876 |

“On Monday evening, April 10, Colonel

Monstery and Regis Senac met at Tammany Hall, New York, to compete

for a stake of 500 dols. and the title of champion-at-arms of the United States

and Spanish America. The match was the result of an

open challenge issued by Colonel Monstery, and promptly accepted by

M. Senac.”

The two fencing masters fought matches with

foils, sabers, rapiers, bayonets and knives. It apparently was a lively and

controversial affair, with arguments from the contestants, judges and the

audience over hits and touches, so that eventually Monstery abandoned the

contest and the referee declared Senac the winner.

Albert Vaughn took up the challenge, but, as

happened more than once, stormed off during one of the bouts, leaving M. Senac

the victor. This may lead one to believe Senac was a somewhat irascible

opponent.

Still, he remained a respected member of the New

York Fencing society. In 1886 he was invited to referee a contest at a

tournament in aid of the Italian Benevolent Society, as well as an exhibition

with one of the champions of Italy, and it seemed no one stormed out.

“I deposit $100 when he says – Ha! Ha! It is too

good! It is magnificent! Look here. I will put up my $500 with the referee on

the very day that he is named. I have it ready. It is in my pocket now. I

replied to his challenge through the papers, and that is quite sufficient.”

Apparently M. Senac saw the need to carry

challenge money in his pocket.

Tronchet

finally got his opportunity to challenge Senac for the championship of America,

defeating Senac in a close struggle. The match was described in an 1887 edition of Frank

Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper as “one of the finest displays of combined

agility and art ever witnessed in this city.”

Finale

While not reaching the popularity of some other

sports, fencing still had strong support among the elite of New York City as an

all-round exercise for building both body and character that still rings true

today. As Richard B. Malchien stated in the 1893 issue of Frank Leslie’s

Popular Monthly “And now, after reading the foregoing, one may naturally

question, ‘But of what use is the practice of fencing nowadays?’ Well, there

are various reasons, and the principal one is exercise, combined with a

fascinating game that can be played at by young and old, weak and strong, male

and female. If you would gain health and keep it, or are desirous of

cultivating a chivalrous disposition, readiness in action, thorough elasticity

and freedom of movement, with a perfect command over all the muscles of the

body, then learn to fence.”

Comments

Post a Comment